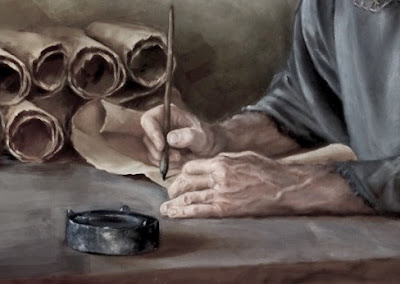

The letter is one of the oldest forms of written communication, becoming a very important means of interaction in the early church. Epistolography, the study of ancient letter writing, is particularly relevant to biblical analysis because the letter is the most common literary genre in the New Testament. Twenty-one of the New Testament’s twenty-seven documents are rendered in letter form. All of Paul's extant writings are letters. The General Epistles exhibit epistolary features, and Hebrews, despite the ongoing debate concerning its genre, has an epistolary conclusion. In addition to these, there are two letters imbedded in Acts (15:23; 23:26), and even the book of Revelation has an epistolary frame.1

Due attention ought to be given to the exegetical implications of this mode of communication whenever New Testament writings are examined. For at least three centuries before and after the beginning of the Christian era, rigid epistolary conventions were in force. Much of our knowledge of ancient letter writing has come since the latter part of the 19th century, with the discovery and subsequent analysis of papyrus letters from Egypt.2

--Kevin L. Moore

Endnotes:

1 See E. S. Fiorenza, “Composition and Structure” 367-81; J. M. Lieu, “Grace to You” 172-73; J. L. White, “Saint Paul” 444.

2 See K. L. Moore, “Epistolography and the Writings of Paul,” in A Critical Introduction to the NT 100-114; also J. H. Greenlee, Introduction to NT Textual Criticism 8-23; B. M. Metzger and B. D. Ehrman, The Text of the NT (4th ed.) 3-33, 206; J. Murphy-O’Connor, Paul the Letter-Writer 1-41.

3 G. J. Bahr suggests that the noticeable difference between Paul’s unimpressive oratory and his impressive letters (2 Cor. 10:10) may be attributable to the writing ability of his secretary (“Letter Writing” 476). W. G. Kümmel notes that the specific references to Paul’s own handwriting were likely included because the letters were read aloud and this was the only way for the listening audience to be made aware of the fact (Introduction 251). In one of the most comprehensive studies on Paul’s use of secretarial services, E. R. Richards concludes that the following letters were probably written by or with the help of an amanuensis: Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Colossians, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, and Philemon (Secretary201).

Related Posts: Study of Ancient History, Study of Ancient Rhetoric, Production of NT Part 1 and Part 2